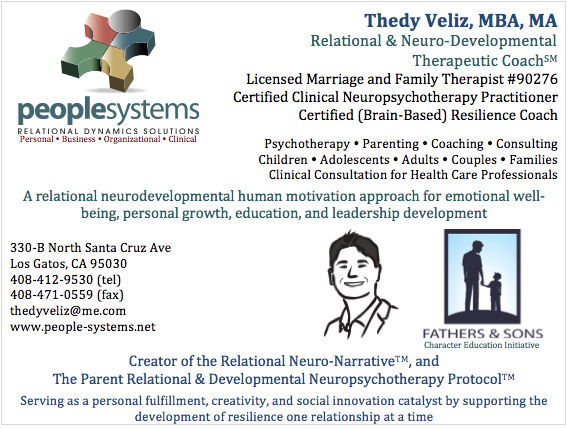

Relational & Neuro-Developmental Therapeutic Coach℠

The People Systems Relational & Neuro-Developmental Approach to Human Dynamics requires the practitioner to carry out a series of diverse functions which result in treatment objectives that encourage my clients to live a resilient lifestyle.

I carry out the role of therapist, educator, and catalyst for a resilient lifestyle. This resilient lifestyle is manifested when clients are able to develop momentum in the important areas of their life such as their significant relationships, family and friends, professional development, finances, leisure activities, spirituality, health and fitness, community involvement, and continued personal growth.

Keeping in mind that we live in a very stressful environment designed to aggressively captivate the attention of consumers, The People Systems Approach requires the practitioner to motivate and inspire clients to make changes in their lifestyle which will allow them to make controllable incongruent choices (Rossouw, 2014) in order to build competing neural networks that will propel the client to move to a more proactive and approach oriented way of living.

What I am saying is that modern clients who live in our stressful fast-paced society need a practitioner that will also serve as a role model and motivator. My clinical experience tells me that it is not enough for a practitioner to do the ‘therapy’ part, as the treatment is incomplete if the client does not quickly apply the therapeutic work by becoming involved in new activities. Insight and understanding is not good enough, crying in session as the client remembers early memories that bring feelings of shame is not good enough. From the People Systems perspective, if the crying does not help the person to take advantage of that emotional release to try something different, the crying won’t be worth the pain.

Due to the above-mentioned multitude of functions that the practitioner must carry out in order to ensure a long-lasting treatment outcome, I have started to see myself as a Relational Neuro-Developmental Therapeutic-Coach℠.

Below, I elaborate more on how I work as a Relational Neuro-Developmental Therapeutic-Coach℠.

Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist

I am a licensed marriage and family therapist, and this means that my work with clients is therapeutic. I assess, diagnose and provide psychotherapeutic treatment to my clients, and I abide by the clinical, legal and ethical standards established by the California Board of Behavioral Sciences, and the California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists. But as I mentioned above, my work does not stop there.

Therapeutic-Coach

There are many types of coaches including sports coaches, voice coaches, life and executive coaches, among many others. Aside from the work that I do as a relational coach in the context of parenting and couples therapy, the ‘coaching’ that I do is closest to what life and executive coaches do, but even when compared to these approaches, my work is substantially different. I feel very comfortable with this distinction because I completed the Coaches Training Institute Life Coaching coursework in 2004. In addition, in January 2017 I enrolled in the NeuroLeadeship Institute’s Coaching Certification program. While I completed the first part of this training (the Brain-Based Conversations Skills Program), I decided to not complete the coaching certification part because the philosophy was significantly different from how I work.

In essence, attempting to complete this training made me realize the difference between a life/executive coach and what I call a therapeutic-coach. In a nutshell, when working as a therapeutic coach, the goal of the coaching is not for the client to achieve a task, but rather to learn about why the task was challenging in the first place so that in the future the client is able to tackle similar tasks on their own. It is when people are able to use their own resources to live their lives that builds resilience and confidence. In the spirit of this, my job is to work myself out of a job by helping my clients to sooner rather than later not need my support. Thus, through the process of therapeutic coaching, the client internalizes a new narrative (what I call a Relational Neuro-Narrative™) about their trust in themselves, in other people and in the future by assisting the client to process the 'self-efficacy blockage' that motivated the client to seek support.

As a therapeutic coach, my job is to constantly co-regulate my clients so that their limbic system is downregulated and their prefrontal cortex is upregulated in order for them to use their executive functioning capabilities to design and implement an alternative lifestyle. However, this is not so automatic and straightforward. If a person has been consumed by feelings of inadequacy for an extended amount of time, this has affected their sense of self-efficacy – their belief in their ideas, gut feelings, instincts, intelligence, and overall wherewithal to achieve their goals. In essence, when people have been disregulated for an extended period of time, they usually develop a distorted idea pertaining to their sense of agency (i.e., their primitive narrative). They are unable to trust others, and don’t have a good vibe when thinking about the future.

In addition, I serve my clients by being a motivating presence, and a catalyst for the development of an alternative Relational Neuro-Narrative™. I don’t tell people what to do, I don’t manage the process of them carrying out their goals, and I don’t hold them accountable. Aside from an overall understanding of where they are and where they want to be by the end of treatment, I don’t even ask them what their detailed goals are.

What happens when we let go of the analytical task-based project management approach is that people start to report to me how they find themselves doing new things, and feeling and thinking in different ways that are baffling to them. When they report these new experiences, I help them integrate this new reality into their new and upgraded life narrative. The client is really the one that is doing the work, and my job is to constantly make the client aware of this, even though at times they might want to attribute it to my support.

I recently completed a brain-based resilience coaching certification program (Rossouw & Rossouw, 2016a) in August 2017 in Melbourne, Australia – a program that was designed from clinical neuroscience findings (Rossouw & Rossouw, 2016b) inspired by the work of Richard Davidson (Davidson & Begley, 2012) on the emotional life of the brain. This Resilience coaching certification included training in the administration of the Predictive 6 Factor Resilience Scale (PR6) in order to measure what I have adapted as the six components of the People Systems treatment objectives: The development, enhancement and maintenance of vision, collaboration, health, composure, tenacity, and reasoning. It is this resilience coaching approach, which is based on clinical neuroscience research findings that my work is most aligned with.

Relational Approach

A highly differentiating feature of the People Systems Approach is that my work is relational. But I am not referring to the fact that therapists work with people that are having relational issues, nor does it refer to the fact that a safe therapeutic relationship is critical to any therapeutic treatment. What I mean is that my job is to facilitate the improvement of my client’s relationships which includes involving the important people in the client’s life in the treatment. I am not referring to my work with couples. This approach applies to every case regardless of the age of the client. For children, adolescents and young adults, I carry out this relational approach by meeting with parents in order to assist them in enhancing their relationship with their children. For individual adult clients, I will as quickly as possible encourage the client to invite the person or persons that they are having the most difficulty with including friends, parents, children, spouses, siblings or other family members to participate in their therapy sessions. In most cases these relational repairs won’t happen from insights during the therapy session while in the presence of a supportive practitioner. To me this is the first step – a rehearsal of sorts, but not the treatment itself.

I believe that if the practitioner does not actively assist the client to improve their important relationships, the only relationship that will be strengthened will be the therapeutic relationship resulting in dependence on therapy (i.e., extended and expensive treatment that won’t result in a long lasting outcome). Instead, clients come to therapy to improve the quality of their relationships since this is how a person improves the way that they view and value themselves and others.

Neuroscience Based

I am also a Certified Clinical Neuropsychotherapy Practitioner. This means that my approach is rooted in the neurodevelopment of the brain, and provides interventions that facilitate the self-regulation of the client by soothing the safety and fear centers of the limbic system of the brain in order to support the robust growth of neural connections between the anxious brain and smart brain. My interest in this field started in 2002 when I attended a weekend seminar at the Esalen Institute which introduced me to attachment theory. I soon started to study the work of Daniel Siegel (Siegel, 1999) and Allan Schore (Schore, 1994; Schore, 2003a; Schore 2003b) and attended the annual Attachment Conference at UCLA which eventually became the Annual Interpersonal Neurobiology Conference. I have attended specialized trainings and/or read and studied publications by the authorities in a collection of clinical, research and theoretical areas which collectively comprise a way of understanding human behavior that is informed by neuroscience. This collection of areas and their respective authorities include:

Attachment Theory

- John Bowlby (Bowlby, 1969; Bowlby, 1973; Bowlby, 1980; Bowlby, 1988)

- Mary Ainsworth (Ainsworth et al., 1978)

- Edward Tronick, PhD. (Tronick, 2007)

- Stephen Porges, PhD. (Porges, 2011)

- Allan Schore, PhD. (Schore, 2002; Schore, 2012)

- Jonathan Baylin, PhD. (Baylin, 2013)

- Louis Cozolino, PhD. (Cozolino, 2014)

- Michael Meaney, PhD. (Meaney, 2010)

- Louis Cozolino (Cozolino, 2002; Cozolino, 2014).

- Claudia Gold, MD (Gold, 2017).

- Sue Gerhardt, PhD. (Gerhardt, 2004).

- Bruce Perry, MD, PhD.

- Pat Ogden, PhD. & Janina Fisher, PhD. (Ogden et al., 2006, Ogden & Fisher, 2015)

- Peter Levine, PhD. (Levine, 2010).

- Bessel van der Kolk, MD. (van der Kolk, 2015)

- Daniel Siegel, MD. (Siegel, 2012; Siegel & Bryson, 2011)

- Daniel Hughes, PhD. (Becker-Weidman & Hughes, 2008; Hughes, 2006; Hughes, 2009; Hughes, 2011; Hughes & Baylin, 2012; Baylin & Hughes, 2016).

Most recently I have been following the work of Professor Peter Rossouw (Rossouw, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016) who serves as president of the International Association of Clinical Neuropsychotherapy, director of the Neuropsychotherapy Institute, and director of Mediros Clinical Solutions through which he provides brain-based education to a broad range of practitioners including psychotherapists. This relationship started during my clinical neuropsychotherapy training in November 2016 in Sydney, Australia resulting in having been invited to present my Parent Relational & Developmental Neuropsychotherapy Protocol™ at the International Conference of Neuropsychotherapy in May 2017 in Brisbane, Australia. Based on the success of this presentation, I have been invited to deliver a keynote presentation on the principles of neuropsychotherpay in working with children, and to run an interactive mini-workshop pertaining to applications of neuropsychotherapy in working with children at the 2nd International Conference of Neuropsychotherapy which is scheduled to take place in May 2018 in Melbourne, Australia.

References

- Ainsworth, M. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Oxford, England: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Baylin, J. (2013). Behavioral Epigenetics & Attachment. The Neuropsychotherapist, 3, 68-79.

- Baylin, J. & Hughes, D. A. (2016). The neurobiology of attachment focused therapy: Enhancing connection and trust in the treatment of children and adolescents (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Becker-Weidman, A., & Hughes, D. (2008). Dyadic developmental psychotherapy: an evidence-based treatment for children with complex trauma and disorders of attachment. Child & Family Social Work, 13(3), 329-337.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Vol. 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss. Vol. 2: Separation. New York: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss. Vol. 3: Loss, sadness, and depression. New York, NY, US: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York, NY, US: Basic Books.

- Cozolino, L. (2002). The neuroscience of psychotherapy: building and rebuilding the human brain (norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Cozolino, L. (2014). Experience-dependent plasticity: The science of epigenetics. The Neuropsychotherapist. 1 (5) Apr-Jun 2014, 40-53.

- Cozolino, L. (2014). The Neuroscience of Human Relationships: Attachment and the Developing Social Brain (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Davidson, R. J., & Begley, S. (2012). The emotional life of your brain: How its unique patterns affect the way you think, feel, and live--and how you can change them. Penguin.

- Gerhardt, S (2004). Why love matters: How affection shapes a baby’s brain. Routledge.

- Gold, C. M. (2017). The developmental science of early childhood: Clinical applications of infant mental health concepts from infance through adolescence. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Hughes, D. A. (2009). Attachment-focused parenting: Effective strategies to care for children. WW Norton & Company.

- Hughes, D. A. (2006). Building the bonds of attachment: Awakening love in deeply troubled children. Jason Aronson.

- Hughes, D. A. (2011). Attachment-focused family therapy workbook. WW Norton & Company.

- Hughes, D. A., & Baylin, J. (2012). Brain-Based Parenting: The Neuroscience of Caregiving for Healthy Attachment (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

- Meaney, M. J. (2010). Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene× environment interactions. Child development, 81(1), 41-79.

- Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy (norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Rossouw, P. J. (2013). The Neuroscience of talking therapies: Implications for therapeutic practice. Neuropsychotherapy in Australia, 24: 3-13.

- Rossouw, P. J. (2014). Neuropsychotherapy: Theoretical underpinnings and clinical applications. Brisbane, AUS: Mediros Pty Ltd.

- Rossouw, P. J. (2015). Resilience: A neurobiological perspective. Neuropsychotherapy in Australia, 31: 3-8.

- Rossouw, P. J. (2016). Certification Training: Clinical Neuropsychotherapy Practitioner Workbook. Brisbane, AUS: Mediros Pty Ltd.

- Rossouw, P. J., & Rossouw, J. G. (2016a). The Predictive 6 Factor Resilience Scale. Clinical Guidelines and Applications. Australia: RForce.

- Rossouw, P. J., & Rossouw, J. G. (2016b). The Predictive 6-Factor Resilience Scale – Neurobiological Fundamentals and Organizational Applications. International Journal of Neuropsychotherapy, 4(1), 31-45.

- Schore, A. N. (1994). Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self: The Neurobiology of Emotional Development. Hillsdale, NJ: Laurence Earbaum Associates.

- Schore, A. N. (2003a). Affect dysregulation and disorders of the self. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Schore, A. N. (2003b). Affect regulation and the repair of the self. New York. NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Schore, A. N. (2002). Advances in neuropsychoanalysis, attachment theory, and trauma research: Implications for self psychology. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 22(3), 433-484.

- Schore, A. N. (2012). The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind, second edition: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Guilford Publications.

- Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2011). The whole-brain child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurture your child's developing mind. Delacorte Press.

- Tronick, E. (2007). The neurobehavioral and social-emotional development of infants and children. WW Norton & Company.

- van Der Kolk, B. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.